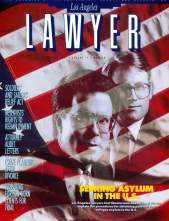

This article, by Attorneys Carl Shusterman and Michael Straus (now an Immigration Judge) appeared, as a cover story, in Los Angeles Lawyer magazine in 1991.

For hundreds of thousands of people threatened by war and other unrest, the United States continues to offer the hope of asylum. Attorneys representing asylum applicants must navigate such cases through a complex system of procedures that can challenge a lawyer’s creativity and perseverance. Successfully guiding an applicant through this system, however, provides a deep sense of accomplishment and satisfaction.

Client Reviews

Legal Guru in All Things Immigration

“Mr. Shusterman and his law firm have represented my family and me very successfully. He is not only a legal guru in all things immigration but even more so he is an exceptional human being because he empathizes with his clients and cares that justice is done.”

- Maria Davari Knapp, Chicago, Illinois

Read More Reviews

Zoom Consultations Available!

Current discussions of U.S. asylum procedures begin with the Refugee Act of 1980. This comprehensive revision of U.S. refugee policy implemented the United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. It also made asylum benefits available to refugees worldwide. Prior to the 1980 act, asylum benefits were limited to applicants from communist or Middle Eastern countries.

For over 10 years the asylum process was governed by interim regulations, which provided temporary mechanisms to adjudicate asylum claims. However, on October 1, 1990, final rules governing the Refugee Act of 1980 went into effect. Though it is hoped that the new regulations will bring more fairness to the asylum process, asylum applicants and their attorneys will continue to face unique and difficult challenges. Attorneys tracking the impact of the new rules on their clients’ cases must start with a thorough knowledge of the manner in which the 1980 act has been implemented by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and interpreted by the courts.

Following the definition of “refugee” set forth in the U.N. protocol, the act set forth the four requirements that must be met for an applicant to qualify for asylum or refugee status:

- The applicant must fear persecution (subjective element);

- The applicant’s fear must be well founded (objective element);

- The persecution must be on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion;

- Favorable exercise of discretion.

An asylum applicant must have an actual and genuine fear of persecution. This is a subjective determination relating to the

applicant’s state of mind. This element is rarely an issue in an asylum claim, because anyone who applies for asylum is likely to express such fear. Nevertheless, it is essential for the applicant to overtly express a fear that he would be persecuted if he were forced to return to his native country.

A more common issue is what constitutes “persecution.” Persecution is defined as harm or suffering inflicted upon the applicant in order to punish him for possessing a belief or characteristic that the persecutor will not tolerate. Sanctions such as torture, killing, jail, and physical attack clearly constitute persecution.

Debates often arise, however, over milder forms of punishment. For example, do government limits on obtaining food rations constitute persecution? In Saballo-Cortez v. I.N.S., the Ninth Circuit held that denial of privileges in purchasing food or obtaining more desirable employment does not constitute persecution. In that case, a Nicaraguan applicant was denied lower food prices and a special work permit because he refused to join a pro- government organization. By contrast, if a government wholly deprives someone of his livelihood, a strong case of persecution can be made.

Another issue that has attracted controversy and litigation is whether punishment for evading compulsory military service can constitute persecution. In M.A. v. I.N.S., the Fourth Circuit, in an en banc opinion, rejected an asylum claim from a Salvadoran who refused service in the nation’s army. His refusal was based on a moral objection to the atrocities committed by the army. The court found that punishment for refusing compulsory military service is not persecution, unless the government in question has been condemned by international bodies and the punishment will be disproportionately severe.

In Devalle v. I.N.S., the Ninth Circuit considered the issue of punishment for deserting the Salvadoran army. The court held that punishment for desertion is not persecution unless the deserter is considered by the army to hold anti-government sympathies. In such a case, the applicant must prove that the government believes he is a political opponent rather than someone who simply does not wish to serve in the army.

The Ninth Circuit addressed the issue of whether a Jehovah’s Witness, whose religion forbids military service, has a claim to persecution in El Salvador, which has no conscientious objector status. In Canas-Segovia v. I.N.S., the Ninth Circuit rejected the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA)’s position that the government must be motivated to persecute. The court held that even though the Salvadoran government had no particular hostility toward Jehovah’s Witnesses, forcing a Jehovah’s Witness to violate a deeply held religious belief nevertheless constitutes persecution.

In Maldonado-Cruz v. I.N.S., the Ninth Circuit found that a person who was forcibly abducted to fight for the Salvadoran guerillas and then escaped might be subject to persecution by the guerillas for desertion. The court determined that escapes had placed themselves in a position precarious enough to provide the basis for a reasonable fear of persecution. This decision distinguished between a military draft, which is established by law, and random abductions by a rebel group.

However, the BIA and other courts of appeals have not followed Maldonado-Cruz and Canas-Segovia. In Perlera-Escobar v. Executive Office for Immigration Review, the 11th Circuit determined that guerilla punishment of deserters is not persecution, because it is not politically motivated. The court held that such punishment is a legitimate measure to enforce military discipline.

Another controversial issue is whether punishment for violating the People’s Republic of China’s policy of limiting each married couple to one child constitutes persecution . In 1989, the BIA found that the purpose of the policy was purely to control population growth. It determined that those who violated the policy unobtrusively and those who violated the policy overtly received similar punishments. In short, punishment for breaking this law could properly be characterized as prosecution, not persecution. In an example of how political consideration sway asylum matters, President George Bush reversed the decision by Executive Order in April, 1990, finding the Chinese policy inherently coercive.”

Generally, persecution must be inflicted by an established government. However, if the established government refuses or is unable to offer protection against persecution instigated by other groups, an asylum claim can be based on persecution by such non-governmental bands as vigilantes or rebels. A significant number of asylum applications from Salvadorans concern persecution by rebels who either control or operate in most parts of that country.

WELL-FOUNDED FEAR OF PERSECUTION

The term “well-founded fear of persecution” has been the subject of considerable litigation. In 1987, the U.S. Supreme Court in I.N.S. v. Cardoza- Fonseca concluded that a well-founded fear means merely a reasonable fear, rather than a fear that is based on a clear probability of persecution. The latter standard had been used by the BIA but rejected by most court of appeals. Cardoza-Fonseca liberalized the standard of proof necessary to show a well-founded fear of persecution.

Under the clear probability standard, the BIA required the applicant to prove that it was more likely than not he would be persecuted. This standard required at least 50 percent chance of persecution.

In Cardoza-Fonseca, the Supreme Court found that a well-founded fear of persecution may exist even if there is less than a 50 percent chance persecution would occur. The court held that even if there were only a 10 percent chance of persecution the applicant would have a well-founded fear of persecution if he returned to his country.

Following Cardoza-Fonseca, the BIA, in Matter of Mogharrabi, determined that one has a well-founded fear of persecution if a reasonable person under the circumstances would fear persecution if he returned to his native country.

The Cardoza-Fonseca decision acknowledged that the term “well-founded fear of persecution” is somewhat ambiguous. Two pre-Cardoza-Fonseca cases illustrate the application of the “reasonable person” test. Both cases involved Iranians who participated in anti-Khomeini political activities in the U.S.

In Farzad v. I.N.S., a student’s car was vandalized at a time when other anti-Khomeini students also had their cars vandalized. However, no direct threats against the applicant or his family had been received and there was no evidence that the vandalism was carried out by the Iranian government. Therefore, the Fifth Circuit determined that a reasonable person would not conclude that the Iranian authorities knew the applicant opposed their government.

In Ghadessi v. I.N.S., the applicant’s parents in Iran were interrogated three times by the authorities about her activities in the U.S. The Ninth Circuit found that, based on this direct government harassment against her family, a reasonable person would fear persecution if returned to Iran.

The media’s general use of the term “political asylum” oversimplifies the issue. Asylum actually may be based on at least one of the following five factors: race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.

The definitions of “particular social group” and “political opinion” have been litigated frequently. Appellate courts and the BIA have differed significantly on these issues.

“Membership in a particular social group” is a difficult concept to define. In Matter of Acosta, the BIA defined “particular social group” as a group of persons who share a common immutable characteristic such as sex, color, kinship ties, family relationship, or common participation in a leadership group. The Ninth Circuit has rejected claims that young Salvadoran urban males who failed to serve in the military or to support the government are members of a particular social group. The court found that this group was too all- encompassing and not sufficiently cohesive and homogeneous .

The Ninth Circuit has issued several opinions concerning the scope of what constitutes “political opinion.” In Bolanos-Hernandez v. I.N.S., the Ninth Circuit held that political neutrality is a political opinion if it was the result of a conscious, affirmative choice. In that case, a former member of a right-wing party and the Salvadoran army had decided to become neutral A guerilla group attempted to recruit him and threatened to kill him if he did not join. Rather than join the guerillas, the applicant fled El Salvador. The court found that the applicant had made an affirmative decision to stay neutral and would be singled out for persecution because of it. Bolanos-Hernandez has not been followed by the BIA and other courts of appeals, all of which have ruled that mere neutrality does not constitute a political opinion.

In many asylum claims, particularly ones made by Central Americans, it is not readily apparent why the person was threatened. In Hernandez-Ortiz v. I.N.S., the Ninth Circuit found that persecution based on political opinion exists if the persecutor imputes or attributes a political opinion to the applicant actually holds or expresses such an opinion.

The applicant in Hernandez-Ortiz feared persecution in El Salvador because the government security forces had threatened, murdered and kidnapped his family members. The court found that when a government uses military force against a group or an individual who has not engaged in conduct providing a legitimate basis for governmental action, the most reasonable presumption is that the government’s actions are politically motivated. Therefore, the security force’s belief that someone is a guerilla sympathizer–and the hostile actions taken because of this belief–constitute persecution based on imputed political opinion.

This concept is illustrated in Mendoza-Perez v. I.N.S., where the applicant, who was involved in land reform, received a threat from a government death squad. The Ninth Circuit found that the most reasonable basis for the threat was the political opinion of the applicant.

EXERCISE OF DISCRETION

Even if an applicant is statutorily qualified for asylum, relief can be denied in the exercise of discretion. The exercise of discretion involves weighing positive and negative factors. Asylum applications are not denied in the exercise of discretion unless adverse factors are present. However, an applicant, in presenting an asylum application, should not forget to present favorable factors, such as close relatives in the U.S., stable employment and the lack of a criminal record.

One very serious adverse factor is the presence of a criminal conviction. The regulations preclude granting asylum to anyone convicted of a “particularly serious” crime, which is one that indicates the perpetrator poses a danger to the community. Many drug trafficking crimes are considered per se particularly serious. However, if a crime is not per se particularly serious, circumstances surrounding the conviction, such as the nature of the conviction, the type of sentence imposed and whether the circumstances indicate the applicant will be a danger to the community, may be considered. A recent Ninth Circuit case held that selling marijuana is not a per se particularly serious crime and the facts surrounding the conviction must be examined.

Another issue involving discretion is “firm resettlement.” Under INS regulations, an applicant will be denied asylum if he was firmly resettled in a third country before coming to the U.S. One is considered resettled if offered permanent resettlement by another nation and given rights similar to those enjoyed by nationals of the third country. This issue occurs frequently in the case of Jewish refugees settling in Israel, which grants automatic citizenship to all Jews. Most Central Americans seeking asylum in the United States travel through Mexico. Merely traveling through a country, however, does not constitute firm resettlement.

Asylum can also be denied in the exercise of discretion if the applicant fraudulently attempts to circumvent the process for overseas admission of refugees. This issue usually arises when an applicant tries to enter the U.S. with a fraudulent passport or visa instead of applying for refugee status overseas. If the applicant has used fraudulent documents solely to flee an oppressive regime, this adverse factor is less likely to lead to a denial. However, if the applicant used fraudulent documents to flee one country where he had obtained sanctuary in order to enter a second safe country, a denial is more likely. This problem happened frequently when Afghanis who had obtained sanctuary in Pakistan tried to enter the U.S. with fraudulent documents. This adverse factor can be overcome with favorable factors, such as family ties in the U.S.

The distinction between refugees and asylees is important. The former are persons outside the U.S. who are seeking resettlement in the U.S. The latter are persons in the U.S. who are afraid to return to their own countries and who seek to remain here.

The INS accepts applications outside the U.S. for anyone seeking to enter the U.S. as a refugee. The agency has several offices throughout the world which interview and process refugee applicants. For example, the INS has officers in Moscow who handle refugee applications from Soviet Jews and Armenians as well as officers in refugee camps in Thailand and Cambodia.

The number of refugee admissions from persons outside the country is limited by the president. In 1989, the ceiling was 116,000 persons. This number is divided into refugee allocations from particular regions of the world, such as Africa, Eastern Europe, East Asia, etc. These allocations are subject to foreign policy considerations. Generally, those regions with which the U.S. is in dispute receive the largest allocations. Regions that are not considered foreign policy priorities usually receive small allocations. For example, in 1989, there was a limit of 2,000 African refugees and 24,500 from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Because allocations are larger for certain regions, backlogs develop, compelling some groups of refugees to wait a considerable period of time before being allowed to come to the U.S. There is no appeal from a denial of a refugee application. Persons admitted to the U.S. as refugees can apply to become permanent residents of the U.S. after one year.

Any alien who is in the U.S. may apply for asylum at an INS district office. An applicant must submit a “request for asylum” (Form I-589) along with supporting documents.

After receipt of the form, an interview will be scheduled with an INS officer. In the past, staffing shortages and insufficient staff knowledge of political conditions in other countries made such interviews a tenuous proposition. The new asylum regulations, however, will create a corps of trained asylum officers who will be assigned exclusively to adjudicate asylum applications.

After the interview, the request for asylum is sent to the Department of State, Bureau of Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs (BHRHA). The BHRHA may express no opinion (this occurs in most applications from Central Americans), provide information on the conditions in the applicant’s country, or state an opinion on the asylum claim. In the past, adjudicators have tended to give great weight to the BHRHA opinion in granting or denying an asylum request. It is to be hoped that more informed adjudicators will not need to rely as heavily on BHRHA opinions and that their judgments will be based to a greater extent on the merits of each case.

If the INS decides to deny the application, it must state the reasons for denial and assess the applicant’s credibility. There is no appeal if the application is denied. The applicant will be referred for deportation proceedings, where the application can be renewed before an immigration judge. If the application is granted, the applicant may remain in the U.S. and apply for permanent residence after one year.

DEPORTATION AND EXCLUSION PROCEEDINGS

A deportation proceeding is a hearing before an immigration judge to determine whether a foreigner may remain in the U.S. Immigration judges are employed by the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), an agency within the Justice Department but independent from the INS. The INS initiates deportation proceedings by charging that someone is in the U.S. illegally. The most common charges are illegal entry, overstaying a visa or committing a crime. Persons seeking to apply for asylum can be subjected to deportation proceedings after being apprehended by the INS or after their asylum application has been denied.

An exclusion hearing conducted by an immigration judge determines whether a foreigner may enter the U.S. Exclusion hearings occur when someone has been refused entry to the U.S. at an airport or land border and wishes to contest the charges against him and/or to apply for asylum.

Another form of relief available in deportation and exclusion proceedings is the withholding of deportation–a mandatory bar that precludes the INS from deporting an alien to a country where he has established that there would be a clear probability of persecution. The clear probability of persecution standard requires a higher degree of proof than the well-founded fear of persecution standard.

Since withholding of deportation is mandatory, it does not involve the exercise of discretion. However, certain persons, including those convicted of particularly serious crimes, are statutorily barred from withholding of deportation. Withholding of deportation may be granted in the exercise of discretion if a request for asylum is denied. However, if someone is granted withholding of deportation but is denied asylum, he is not eligible to apply for permanent residence on this basis. In addition, if the INS can find a third country that is willing to accept him, he can be deported to that country. Thus, someone granted withholding of deportation consequently is in a virtual state of limbo.

When an applicant appears before the immigration judge, he is requested to state whether he seeks relief from deportation. At that time, a request for asylum should be made. An asylum applicant must file a completed application form and any supporting documentary evidence. The application is then forwarded to the BHRHA.

After receipt of the BHRHA opinion, the application is heard by an immigration judge and a taped record of the hearing is made. The applicant testifies along with any witness and all are subject to cross-examination by an INS trial attorney. The immigration judge frequently questions the witnesses. Following the testimony, the immigration judge renders a decision, usually an oral one.

If the immigration judge denies a request for asylum, the decision can be appealed to the BIA. Like immigration judges, the BIA is under the EOIR. While an appeal to the BIA is pending, the applicant cannot be deported. When an appeal is filed, the tape recording of the deportation hearing is transcribed. When preparation of the transcript is completed, copies are mailed to the applicant and the INS. Each side is given the opportunity to submit a legal brief. The BIA then issues a written decision based on the record and the briefs submitted, though oral arguments also may be considered.

In a deportation hearing, the applicant may submit a “petition for review” to the U.S. Court of Appeals if the BIA dismisses his appeal. A denial in an exclusion case may be challenged in a U.S. district court by requesting the issue of a writ of habeas corpus. If the BIA denies a request for asylum in a deportation case, the petition acts as an automatic stay of deportation. There is no automatic stay of deportation in an exclusion case.

An asylum claim can be raised after the immigration judge or the BIA has issued a decision through a motion to reopen. A motion to reopen must allege new and previously unavailable evidence and must demonstrate a prima facie case for asylum. The immigration judge or the BIA may deny the motion on statutory grounds and/or in the exercise of discretion.

In INS v. Abudu, the Supreme Court gave the immigration judge and the BIA wide discretion and deference in denying motion to reopen. The applicant in Abudu was a citizen of Ghana who had not applied for asylum during a 1982 deportation proceeding and was ordered deported. The applicant appealed the deportation ruling and thus was able to remain in the U.S. In 1984, a high official in Ghana’s government made a surprise visit to the applicant, who was a physician, and invited him to return to Ghana to help serve the country’s medical needs. The applicant concluded that the offer was a ploy designed to place him in a position where he would be forced to reveal the whereabouts of his brother and several other enemies of the Ghana government. The physician filed a motion to reopen his deportation proceedings, which the BIA denied.

The Ninth Circuit found that the applicant had presented a prima facie case for asylum. The court required the BIA to draw all reasonable inferences in the applicant’s favor, similar to the procedure used on a motion for summary judgment.

The Supreme Court reversed, holding that a strict standard applies to motions to reopen, analogous to that used in a motion to reopen for a new trial in a criminal case. The Supreme Court held that decisions by the BIA and immigration judges on motions to reopen should be accorded great deference. Therefore, anyone considering filing for asylum should request the opportunity to file the application before the immigration judge issues a decision.

THE NEW ASYLUM REGULATIONS

A key change provided in the new regulations is the creation of a corps of specially trained asylum officers. Asylum officers now report directly to the INS Central Office for Refugees, Asylum, and Parole in Washington, D.C., rather than to the local INS district directors. Asylum officers will receive specialized training on human rights conditions and international law. There will be a documentation center for the collection and dissemination of information on human rights worldwide for asylum officers to use. This center will collect non-governmental as well as governmental reports, providing asylum officers with a broader perspective on human rights issues than was previously available. It is anticipated that this should reduce reliance on BHRHA opinions. Asylum officers are expected to be trained and performing their duties by the spring of 1991. It is hoped that this measure will allow for more fair and uniform adjudication of asylum applications by the INS.

The interim regulations required an opinion from the BHRHA in order to adjudicate an asylum application. The new rules still require that all applications be sent to the BHRHA. However, if the BHRHA does not respond within 60 days, the application can be adjudicated without BHRHA input.

Another provision in the new asylum regulations relates to the burden of proof. It states that past persecution is a basis for asylum in certain circumstances. More important, the regulations provide that if an applicant can establish that there is a pattern or practice of persecuting a group of persons similarly situated to the applicant, he need not prove he would be singled out if he can establish he is a member of that particular group. This provision will ease the burden of proof for many asylum applicants.

It will be interesting to see how these regulations will be implemented and how they will affect applicants from certain countries. Salvadorans and Guatemalans, for example, have had difficulty obtaining asylum. In 1989, 2 percent of Salvadorans and less than 1 percent of Guatemalans were granted asylum in the INS Western Region. The regulations may allow for the granting of asylum to more Central Americans.

An asylum case rests mostly on facts and how they are presented. Very often, however, applicants have no written evidence to support their claim. The only evidence that they can present is their own testimony.

A recent case illustrates both the drama and the difficulty inherent in substantiating a request for asylum. The applicant, an engineer from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), escaped from his country after the communist takeover in 1949. He later returned to the PRC, where he was arrested for acting as a U.S. spy, tortured an imprisoned for 20 years. He eventually escaped, traveled to Beijing and managed to obtain a visitor’s visa to the U.S. through the offices of George Bush, then U.S. envoy to the PRC.

Upon returning to the U.S., the applicant attempted to recover his green card. Because he had been in a foreign country well beyond the one-year limitation permitted to green-card holders, the INS rejected his application.

Prior to obtaining legal representation, the applicant filed for political asylum. Attorneys usually discourage such affirmative filings in all but the strongest cases because of the likelihood that the application will be denied by the INS. This is particularly true in cases where the applicant is from a country friendly to the U.S.

None of the applicant’s statements could be documented. However, a convincing case was made through the presentation of exhaustive details in an unusually lengthy affidavit. The facts the applicant revealed about U.S. intelligence gathering, the knowledge he showed of U.S. operatives and his vivid memory fleshed out an account of events which proved irrefutable. The application was approved.

In any asylum case, the question on the application form must be filled out completely. The importance of a detailed, chronological affidavit cannot be overemphasized. Sketchy and uninformative applications are often denied by immigration examiners or judges. Many application also fail because of inconsistencies between statements in the application and the applicant’s oral testimony. Careful preparation of the application is crucial to the success of an asylum application.

It also is important to submit background information regarding conditions in the country from which the applicant has fled. The State Department annually publishes a human rights report for every country in the world, as do many human rights organizations such as Amnesty international. Newspaper and magazine articles may be relevant. The testimony of witnesses to the events, or expert witnesses familiar with conditions in specific countries, can be of great importance.

When the only evidence the alien can present is his own testimony, the adjudicator’s assessment of his credibility is crucial. The testimony must be believable, consistent and sufficiently detailed to provide a plausible and coherent account of his basis for persecution. An immigration judge’s credibility findings are given great weight on appeal. An adverse credibility finding, however, requires specific and cogent reasoning by the immigration judge.

During the asylum hearing, it is the role of the attorney to question his client thoroughly on the facts relevant to the asylum claim. It is important not to allow the client to state any conclusions without laying out a cogent ground for each conclusion.

(To observe how the asylum procedure was substantially altered in 1995, see the following article.)